Gertrude Bell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell,

Gertrude Bell was born on 14 July 1868 in Washington New Hall—now known as Dame Margaret Hall—in

Gertrude Bell was born on 14 July 1868 in Washington New Hall—now known as Dame Margaret Hall—in

In 1905, she returned to Greater Syria. She met Mark Sykes, then a British traveller. The two quarrelled and shared a mutual dislike of each other that would last until 1912, when they made up. She concluded her trip visiting archaeological sites in Asia Minor and visiting Constantinople. She published her observations of the Middle East in the 1907 book ''Syria: The Desert and the Sown''. In it she vividly described, photographed, and detailed her trip to Greater Syria including Damascus, Jerusalem,

In 1905, she returned to Greater Syria. She met Mark Sykes, then a British traveller. The two quarrelled and shared a mutual dislike of each other that would last until 1912, when they made up. She concluded her trip visiting archaeological sites in Asia Minor and visiting Constantinople. She published her observations of the Middle East in the 1907 book ''Syria: The Desert and the Sown''. In it she vividly described, photographed, and detailed her trip to Greater Syria including Damascus, Jerusalem,  In 1913, she completed her last and most arduous Arabian journey, travelling about 1800 miles from Damascus to the politically volatile Ha'il, back up across the Arabian peninsula to

In 1913, she completed her last and most arduous Arabian journey, travelling about 1800 miles from Damascus to the politically volatile Ha'il, back up across the Arabian peninsula to

In November 1915, Bell was summoned to

In November 1915, Bell was summoned to

Bell, Cox and Lawrence were among a select group of "Orientalists" convened by Churchill to attend the conference in Cairo to determine the internal boundaries of the British mandates from within the territory Britain had claimed during the

Bell, Cox and Lawrence were among a select group of "Orientalists" convened by Churchill to attend the conference in Cairo to determine the internal boundaries of the British mandates from within the territory Britain had claimed during the

The Sharifan solution prevailed, and Faisal was presented to Iraq as the new king. The main local candidate for leadership who had opposed the selection of Faisal, Sayyid Talib, was arrested and exiled in April 1921 after being invited to tea with Percy Cox's wife, at Bell's suggestion and with Cox's assent; Bell viewed Talib as a potential rebel if left unchecked.

Bell served in the Iraq British High Commission advisory group throughout the 1920s and was an integral part of the administration of Iraq in Faisal's first years. Upon Faisal's arrival in 1921, Bell advised him on local questions, including matters involving tribal geography, tribal leadership, and local business. Faisal was crowned king of Iraq on 23 August 1921. Referred to in

The Sharifan solution prevailed, and Faisal was presented to Iraq as the new king. The main local candidate for leadership who had opposed the selection of Faisal, Sayyid Talib, was arrested and exiled in April 1921 after being invited to tea with Percy Cox's wife, at Bell's suggestion and with Cox's assent; Bell viewed Talib as a potential rebel if left unchecked.

Bell served in the Iraq British High Commission advisory group throughout the 1920s and was an integral part of the administration of Iraq in Faisal's first years. Upon Faisal's arrival in 1921, Bell advised him on local questions, including matters involving tribal geography, tribal leadership, and local business. Faisal was crowned king of Iraq on 23 August 1921. Referred to in

In October 1922, King Faisal appointed Bell as Honorary Director of Antiquities, a task suited to her experience and love of archaeology. Several notable excavations took place during Bell's tenure, with Bell involved in the cataloguing and distribution of antiquities. Leonard Woolley conducted extensive excavations of the city of Ur from 1922–1934. In 1924, Bell personally invited

In October 1922, King Faisal appointed Bell as Honorary Director of Antiquities, a task suited to her experience and love of archaeology. Several notable excavations took place during Bell's tenure, with Bell involved in the cataloguing and distribution of antiquities. Leonard Woolley conducted extensive excavations of the city of Ur from 1922–1934. In 1924, Bell personally invited

The Gertrude Bell Project

based a

Newcastle University Library

The Gertrude Bell Archive

* * * *

(photographs)

Lifestory of Gertrude Bell, from "Lives of the First World War"

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Bell, Gertrude 1868 births 1926 deaths 19th-century British women writers 19th-century English writers 20th-century archaeologists 20th-century British women writers 20th-century English writers 20th-century geographers Alumni of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford Anti-suffragists British women archaeologists British women historians British women in World War I British women travel writers Burials in Iraq Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Daughters of baronets English Arabists English archaeologists English explorers English mountain climbers English travel writers Explorers of Arabia Explorers of Asia Female climbers Female explorers Female wartime spies Holy Land travellers Interwar-period spies People educated at Queen's College, London People from Middlesbrough People from Washington, Tyne and Wear Victorian women writers Witnesses of the Armenian genocide Women geographers World War I spies for the United Kingdom

CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(14 July 1868 – 12 July 1926) was an English writer, traveller, political officer, administrator, and archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

. She spent much of her life exploring and mapping the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, and became highly influential to British imperial policy-making as an Arabist due to her knowledge and contacts built up through extensive travels. During her lifetime, she was highly esteemed and trusted by British officials such as High Commissioner for Mesopotamia Percy Cox

Major-General Sir Percy Zachariah Cox (20 November 1864 – 20 February 1937) was a British Indian Army officer and Colonial Office administrator in the Middle East. He was one of the major figures in the creation of the current Middle East.

...

, giving her great influence. She participated in both the 1919 Paris Peace Conference

Events

January

* January 1

** The Czechoslovak Legions occupy much of the self-proclaimed "free city" of Pressburg (now Bratislava), enforcing its incorporation into the new republic of Czechoslovakia.

** HMY ''Iolaire'' sinks off the c ...

(briefly) and the 1921 Cairo Conference, which helped decide the territorial boundaries and governments of the post-War Middle East as part of the partition of the Ottoman Empire

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 19181 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was ...

. Bell believed that the momentum of Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

was unstoppable, and that the British government should ally with nationalists rather than stand against them. Along with T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

, she advocated for independent Arab states in the Middle East following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and supported the installation of Hashemite

The Hashemites ( ar, الهاشميون, al-Hāshimīyūn), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916–1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921� ...

monarchies in what is today Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

and Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

.

Bell was raised in a privileged environment that allowed her an education at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, to travel the world, and to make the acquaintance of people who would become influential policy-makers later. In her travels, she became an excellent mountain climber

Mountaineering or alpinism, is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending tall mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas. Indoor climbing, sport climbing, an ...

and horseback rider. She expressed great affection for the Middle East, visiting Qajar Iran

Qajar Iran (), also referred to as Qajar Persia, the Qajar Empire, '. Sublime State of Persia, officially the Sublime State of Iran ( fa, دولت علیّه ایران ') and also known then as the Guarded Domains of Iran ( fa, ممالک م ...

, Syria-Palestine

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, and Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

. She participated in archaeological digs during a time period of great ferment and new discoveries, and personally funded a dig at Binbirkilise

Binbirkilise (literally: Thousand and One Churches) is a region in the antique Lycaonia, in modern Karaman Province of Turkey, known for its around fifty Byzantine church ruins.

The region is located on the northern slopes of the volcano Kara ...

in Asia Minor. She travelled through the Ha'il region in the northern part of the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate ...

during an extensive trip in 1913–1914, and was one of very few Westerners to have seen the area at the time. The outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914, and the Ottoman Empire's entry into the war a few months later on the side of Germany, upended the status quo in the Middle East. She briefly joined the Arab Bureau

The Arab Bureau was a section of the Cairo Intelligence Department established in 1916 during the First World War, and closed in 1920, whose purpose was the collection and dissemination of propaganda and intelligence about the Arab regions of ...

in Cairo, where she worked with T. E. Lawrence. At the request of family friend Lord Hardinge, Viceroy of India, she joined the British administration in Ottoman Mesopotamia in 1917, where she served as a political officer and as the Oriental Secretary to three High Commissioners: the only woman in such high-ranking civil roles in the British Empire. Bell also supported the cause of the largely urban Sunni population in their attempts to modernise Iraq.

She spent much of the rest of her life in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

and was a key player in the nation-building of what would eventually become the Kingdom of Iraq

The Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq ( ar, المملكة العراقية الهاشمية, translit=al-Mamlakah al-ʿIrāqiyyah ʾal-Hāshimyyah) was a state located in the Middle East from 1932 to 1958.

It was founded on 23 August 1921 as the Kingdo ...

. She met and befriended a large number of Iraqis in both the cities and the countryside, and was a confidante and ally of Iraq's new King Faisal. Toward the end of her life, she was sidelined from Iraqi politics. Perhaps seeing that she still needed something to occupy her, Faisal appointed her the Honorary Director of Antiquities of Iraq, where she returned to her original love of archaeology. In that role, she helped modernize procedures and catalogue findings, all of which helped prevent unauthorized looting of artifacts. She supported education for Iraqi women, served as president of the Baghdad library (the future Iraq National Library), and founded the Iraq Museum

The Iraq Museum ( ar, المتحف العراقي) is the national museum of Iraq, located in Baghdad. It is sometimes informally called the National Museum of Iraq, a recent phenomenon influenced by other nations' naming of their national museum ...

as a place to display the country's archaeological treasures. She died in 1926 of an overdose of sleeping pills

Hypnotic (from Greek ''Hypnos'', sleep), or soporific drugs, commonly known as sleeping pills, are a class of (and umbrella term for) psychoactive drugs whose primary function is to induce sleep (or surgical anesthesiaWhen used in anesthesia ...

in what was possibly a suicide, although she was in ill health regardless.

Bell wrote extensively. She translated a book of Persian poetry; published multiple books describing her travels, adventures, and excavations; and sent a steady stream of letters back to England during World War I that influenced government thinking in an era when few English people were familiar with the contemporary Middle East.

Early life

Gertrude Bell was born on 14 July 1868 in Washington New Hall—now known as Dame Margaret Hall—in

Gertrude Bell was born on 14 July 1868 in Washington New Hall—now known as Dame Margaret Hall—in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, County Durham

County Durham ( ), officially simply Durham,UK General Acts 1997 c. 23Lieutenancies Act 1997 Schedule 1(3). From legislation.gov.uk, retrieved 6 April 2022. is a ceremonial county in North East England.North East Assembly �About North East E ...

, England. Her family was wealthy, which enabled both her higher education and her travels. Her grandfather was the ironmaster

An ironmaster is the manager, and usually owner, of a forge or blast furnace for the processing of iron. It is a term mainly associated with the period of the Industrial Revolution, especially in Great Britain.

The ironmaster was usually a large ...

Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell, an industrialist and a Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

Member of Parliament between 1875 and 1880. Mary ( Shield) Bell, the daughter of John Shield of Newcastle-on-Tyne and Gertrude's mother, died in 1871 while giving birth to a son, Maurice Bell (later the 3rd Baronet). Gertrude Bell was just three at the time, and the death led to a lifelong close relationship with her father, Sir Hugh Bell, 2nd Baronet, a progressive capitalist and mill owner who made sure his workers were well paid. Throughout her life, Gertrude consulted on matters great and small with her father, her personal role model. In particular, Hugh shared his knowledge of government and access to highly-placed officials with Gertrude.

When Gertrude was seven years old, her father remarried, providing her a stepmother, Florence Bell (née Olliffe), and eventually, three half-siblings. Florence Bell was a playwright and author of children's stories, as well as the author of a study of Bell factory workers. She instilled concepts of duty and decorum in Gertrude. She also recognized her intelligence and contributed to her intellectual development by ensuring she received an excellent schooling. Florence Bell's activities with the wives of Bolckow Vaughan

Bolckow, Vaughan & Co., Ltd was an English steelmaking, ironmaking and mining company founded in 1864, based on the partnership since 1840 of its two founders, Henry Bolckow and John Vaughan (ironmaster), John Vaughan. The firm drove the dramat ...

ironworkers in Eston

Eston is a Village in the borough of Redcar and Cleveland, North Yorkshire, England. The ward covering the area (as well as Lackenby, Lazenby and Wilton) had a population of 7,005 at the 2011 census. It is part of Greater Eston, which include ...

, near Middlesbrough

Middlesbrough ( ) is a town on the southern bank of the River Tees in North Yorkshire, England. It is near the North York Moors national park. It is the namesake and main town of its local borough council area.

Until the early 1800s, the a ...

, may have helped influence her step-daughter's later promotion of education for Iraqi women. Some biographies suggest the loss of her mother Mary caused underlying childhood trauma, revealed through periods of depression and risky behaviour. While this loss surely marked her, Gertrude and Florence had a positive and lifelong relationship.

From 1883 to 1886, Gertrude Bell attended Queen's College in London, a prestigious school for girls. At the age of 17, she then studied at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. History was one of the few subjects women were allowed to study, due to the many restrictions imposed on them at the time. She specialised in modern history, and she was the first woman to graduate in Modern History at Oxford with a first class honours degree

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

, a feat she achieved in only two years. Eleven people graduated that year. Nine were recorded because they were men, and the other two were Bell and Alice Greenwood. However, the two women were not awarded academic degrees. It was not until 1920 that Oxford treated women equally with men in this respect.

Personal life

Bell never married or had children. After graduating from Oxford, she spent two and a half years, from 1890 to 1892, attending the London social rounds of balls and banquets where eligible young men and women paired off, but failed to find a match. After arriving in Persia in 1892, she courted Henry Cadogan, a mid-ranking British diplomat in Tehran, but was refused permission to marry him after her father discovered that Cadogan was deeply in debt and not her social equal. Cadogan died in 1893; Bell received the news via telegram. She befriended British colonial administrator SirFrank Swettenham

Sir Frank Athelstane Swettenham (28 March 1850 – 11 June 1946) was a British colonial administrator who became the first Resident general of the Federated Malay States, which brought the Malay states of Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan and ...

on a visit to Singapore with her brother Hugo in 1903 and maintained a correspondence with him until 1909. She had a "brief but passionate affair" with Swettenham following his retirement to England in 1904. She had an unconsummated affair with Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

Charles Doughty-Wylie

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Hotham Montagu "Richard" Doughty-Wylie, (23 July 1868 – 26 April 1915) was a British Army officer and an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be ...

, a married man, with whom she exchanged love letters from 1913 to 1915. Doughty-Wylie died in April 1915 during the Gallipoli Campaign, a loss which devastated Bell.

Travels and writings

Bell's uncle, Sir Frank Lascelles, was British minister (similar to ambassador) atTehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. Bell travelled to Persia to visit him, arriving in May 1892. She stayed for around six months and loved the experience; she called Persia "paradise" in a letter home. She described her experiences in her book ''Persian Pictures'', which was published in 1894. She spent much of the next decade travelling around the world, mountaineering

Mountaineering or alpinism, is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending tall mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas. Indoor climbing, sport climbing, a ...

in Switzerland, and developing a passion for archaeology and languages. She became fluent in Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

, Persian (Farsi), French, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, and Turkish. In 1897, she published a well-regarded translation from Persian into English of the poems of The Divān of Hafez

''The Divān'' of Hafez (Persian: دیوان حافظ) is a collection of poems written by the Iranian poet Hafez. Most of these poems are in Persian, but there are some macaronic language poems (in Persian and Arabic) and a completely Arabic gha ...

; her work was later praised by Edward Denison Ross

Sir Edward Denison Ross (6 June 1871 – 20 September 1940) was an orientalist and linguist, specializing in languages of the Middle East, Central and East Asia. He was the first director of the University of London's School of Oriental Studies ( ...

, E. Granville Browne, and others. She had also practised horseback riding

Equestrianism (from Latin , , , 'horseman', 'horse'), commonly known as horse riding (Commonwealth English) or horseback riding (American English), includes the disciplines of riding, driving, and vaulting. This broad description includes the ...

from a young age, a skill that would aid her in her travels.

In 1899, Bell again went to the Middle East. She visited Palestine and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

that year and in 1900, on a trip from Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

to Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, she became acquainted with the Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

living in Jabal al-Druze.

Between 1899 and 1904, she climbed a number of mountains, including the La Meije

La Meije is a mountain in the Massif des Écrins range, located at the border of the Hautes-Alpes and Isère ''départements''. It overlooks the nearby village of La Grave, a mountaineering centre and ski resort, well known for its off-piste ...

and Mont Blanc

Mont Blanc (french: Mont Blanc ; it, Monte Bianco , both meaning "white mountain") is the highest mountain in the Alps and Western Europe, rising above sea level. It is the second-most prominent mountain in Europe, after Mount Elbrus, and i ...

, and recorded 10 new paths or first ascents in the Bernese Alps

, topo_map= Swiss Federal Office of Topography swisstopo

, photo=BerneseAlps.jpg

, photo_caption=The Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau

, country= Switzerland

, subdivision1_type=Cantons

, subdivision1=

, parent= Western Alps

, borders_on=

, l ...

in Switzerland. One Alpine peak in the Bernese Oberland

The Bernese Oberland ( en, Bernese Highlands, german: Berner Oberland; gsw, Bärner Oberland; french: Oberland bernois), the highest and southernmost part of the canton of Bern, is one of the canton's five administrative regions (in which context ...

, the Gertrudspitze, was named after her after she and her guides Ulrich and Heinrich Fuhrer first traversed it in 1901. However, she failed in an attempt of the Finsteraarhorn

The Finsteraarhorn () is a mountain lying on the border between the cantons of Bern and Valais. It is the highest mountain of the Bernese Alps and the most prominent peak of Switzerland. The Finsteraarhorn is the ninth-highest mountain and thi ...

in August 1902, when inclement weather including snow, hail and lightning forced her to spend "forty eight hours on the rope" with her guides, clinging to the rock face in terrifying conditions that nearly cost her her life. She did some further climbing in the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

during a trip through North America in 1903, but eased up on her mountaineering in later years.

In 1905, she returned to Greater Syria. She met Mark Sykes, then a British traveller. The two quarrelled and shared a mutual dislike of each other that would last until 1912, when they made up. She concluded her trip visiting archaeological sites in Asia Minor and visiting Constantinople. She published her observations of the Middle East in the 1907 book ''Syria: The Desert and the Sown''. In it she vividly described, photographed, and detailed her trip to Greater Syria including Damascus, Jerusalem,

In 1905, she returned to Greater Syria. She met Mark Sykes, then a British traveller. The two quarrelled and shared a mutual dislike of each other that would last until 1912, when they made up. She concluded her trip visiting archaeological sites in Asia Minor and visiting Constantinople. She published her observations of the Middle East in the 1907 book ''Syria: The Desert and the Sown''. In it she vividly described, photographed, and detailed her trip to Greater Syria including Damascus, Jerusalem, Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

, Alexandretta, and the lands of the Druze and of the Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert and A ...

. ''The Desert and the Sown'' was well-received in the western world; the book received positive reviews and was a success. A notable epithet

An epithet (, ), also byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) known for accompanying or occurring in place of a name and having entered common usage. It has various shades of meaning when applied to seemingly real or fictitious people, di ...

of Bell's came from her trip to Syria, where one particular compliment from a Bani Sakher tribesman she recorded became part of her later public image: "''Mashallah

''Mashallah'' ( ar, مَا شَاءَ ٱللَّٰهُ, '), also written Masha'Allah, Maşallah (Turkey and Azerbaijan), Masya Allah (Malaysia and Indonesia), Maschallah (Germany), and Mašallah ( Bosnia), is an Arabic phrase that is used to expre ...

! Bint aarab.''" Literally, it meant "As God wills it, a daughter of the Arabs," but she translated it as being called a "daughter of the desert."

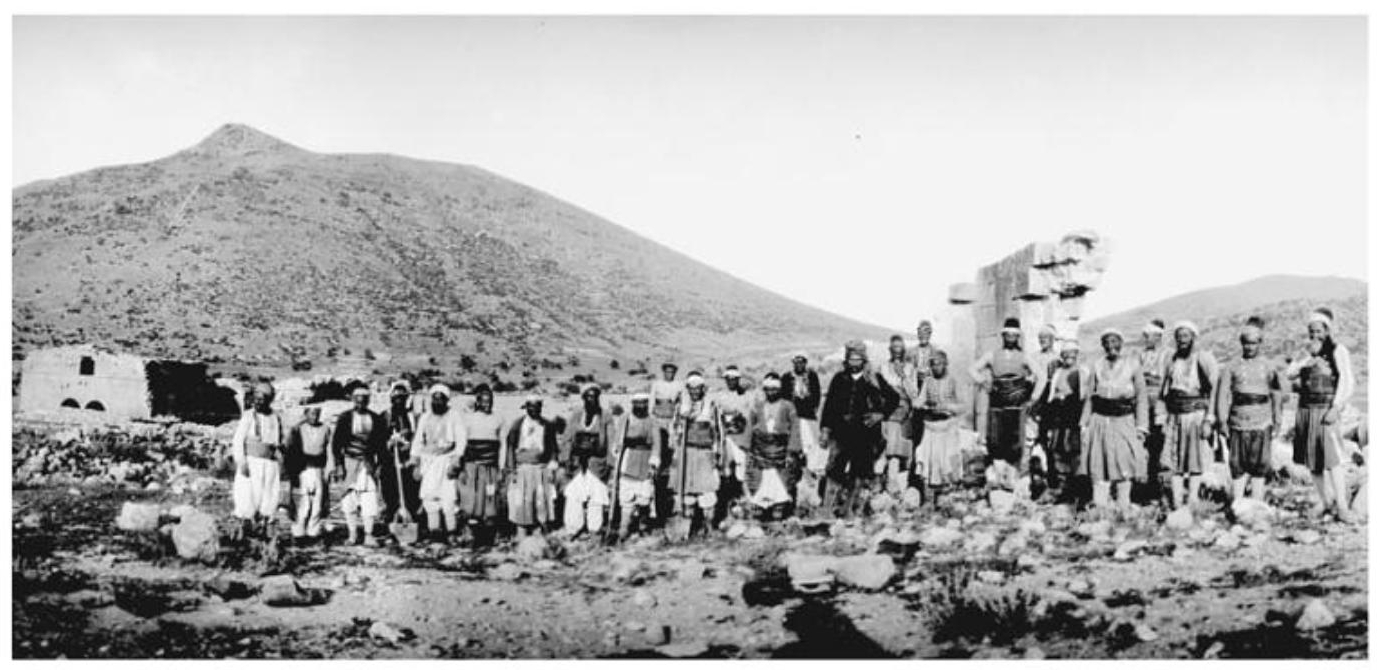

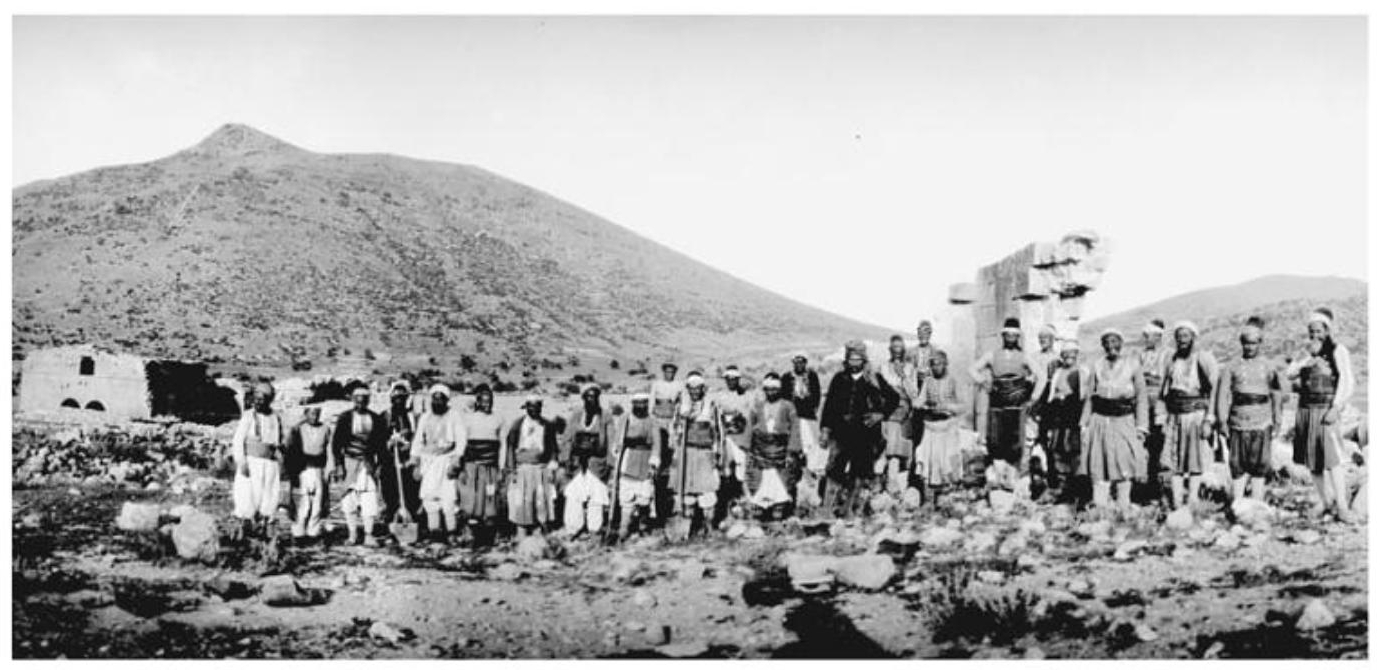

In March 1907, Bell journeyed back to Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

(Anatolia) and began to work with Sir William M. Ramsay, an archaeologist and New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

scholar. The pair and their staff performed excavations of destroyed buildings and churches that dated from the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

era in Binbirkilise

Binbirkilise (literally: Thousand and One Churches) is a region in the antique Lycaonia, in modern Karaman Province of Turkey, known for its around fifty Byzantine church ruins.

The region is located on the northern slopes of the volcano Kara ...

, which she funded and planned. The results were chronicled in the book ''A Thousand and One Churches''.

In January 1909, Bell left for Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

. She visited the Hittite city of Carchemish

Carchemish ( Turkish: ''Karkamış''; or ), also spelled Karkemish ( hit, ; Hieroglyphic Luwian: , /; Akkadian: ; Egyptian: ; Hebrew: ) was an important ancient capital in the northern part of the region of Syria. At times during it ...

, photographed the relief carvings in Halamata Cave

Halamata Cave is an archaeological site near Duhok in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The caves contain the Assyrian relief carvings known as the Maltai reliefs.

The cave is located seven kilometres south-west of Dohuk, above the village of Gever ...

, mapped and described the ruin of Ukhaidir, and travelled on to Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

and Najaf

Najaf ( ar, ٱلنَّجَف) or An-Najaf al-Ashraf ( ar, ٱلنَّجَف ٱلْأَشْرَف), also known as Baniqia ( ar, بَانِيقِيَا), is a city in central Iraq about 160 km (100 mi) south of Baghdad. Its estimated popula ...

. In Carchemish, she consulted with the two archaeologists on site, T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

and Reginald Campbell Thompson

Reginald Campbell Thompson (21 August 1876 – 23 May 1941) was a British archaeologist, assyriologist, and cuneiformist. He excavated at Nineveh, Ur, Nebo and Carchemish among many other sites.

Biography

Thompson was born in Kensington, ...

. She struck up a friendship with Lawrence, and the two would trade letters in the following years. Both Bell and Lawrence had attended Oxford and earned a First Class Honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

in Modern History, both spoke fluent Arabic, and both travelled extensively in the Arabian desert and established ties with the local tribes. In 1910, Bell visited the Munich exhibition ''Masterpieces of Muhammadan Art''. In a letter to her stepmother, she recounts how she had the research room to herself and spoke to some Syrians from Damascus who were part of the ethnographic section of the exhibition. She wrote a book on her journey and the archaeological work, ''Amurath to Amurath'', as well as a journal article.

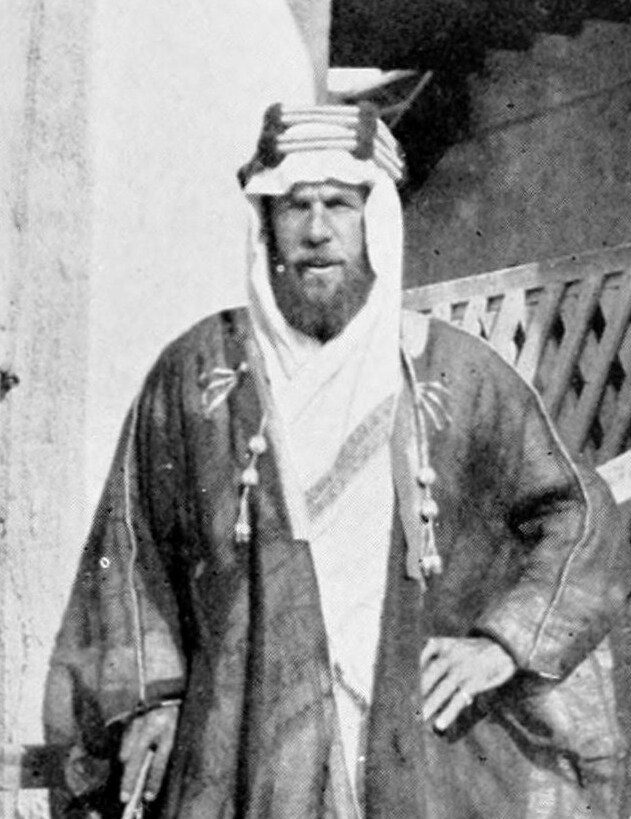

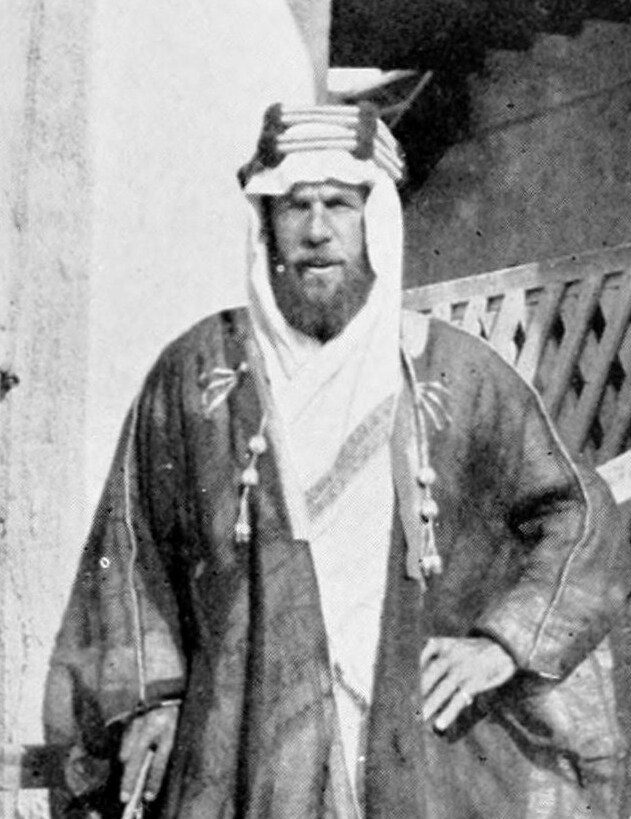

In 1913, she completed her last and most arduous Arabian journey, travelling about 1800 miles from Damascus to the politically volatile Ha'il, back up across the Arabian peninsula to

In 1913, she completed her last and most arduous Arabian journey, travelling about 1800 miles from Damascus to the politically volatile Ha'il, back up across the Arabian peninsula to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

and from there back to Damascus. She was only the second foreign woman after Lady Anne Blunt

Anne Isabella Noel Blunt, 15th Baroness Wentworth (née King-Noel; 22 September 1837 – 15 December 1917), known for most of her life as Lady Anne Blunt, was co-founder, with her husband the poet Wilfrid Blunt, of the Crabbet Arabian Stud in E ...

to visit Ha'il. Unbeknownst to outsiders, the Rashidi dynasty

The Rasheed dynasty, also called Al Rasheed or the House of Rasheed ( ar, آل رشيد ; ), was a historic Arabian House or dynasty that existed in the Arabian Peninsula between 1836 and 1921. Its members were rulers of the Emirate of Ha'il an ...

had been ravaged by both war with Ibn Saud's forces and internecine rivalries; the Emir and oldest dynasty member was only 16 years old after assassinations and disputes had killed others of the bloodline. Bell was held prisoner in the city for eleven days before being released. She wrote afterward that "In Hayil, murder is like the spilling of milk." At the conclusion of her trip in Baghdad, Bell met the influential Naqib, Abd Al-Rahman Al-Gillani

Qutb-ul Aqtaab Naqib Al Ashraaf Syed Abd ar-Rahman al-Qadri al Gillani ( ar, عبد الرحمن الكيلاني النقيب; 11 January 1841 – 13 June 1927) was the first prime minister of Iraq, and its head of state. Al Gillani was chosen i ...

, who would be an important political figure later after the end of Ottoman rule. Bell's travels resulted in her being elected a Fellow of the Geographical Society in 1913; she was awarded a medal from them in 1914, then another in 1918.

Throughout her travels Bell established close relations with local inhabitants and tribes across the Middle East. While she could meet with the wives and daughters of local notables without it being a breach of propriety, a possibility denied male travellers, she did not take advantage of this much; she was only mildly curious about the lives of Arab women. Her main focus was on meeting and knowing the influential in Arab society, the male shaiks and leaders.

War and political career

Outbreak of war

The British entered World War I in August 1914, and the Ottoman Empire entered the war in late October to early November. At the suggestion ofWyndham Deedes

Brigadier-General Sir Wyndham Henry Deedes, CMG, DSO(10 March 1883 – 2 September 1956) was a British Army officer and civil administrator. He was the Chief Secretary to the British High Commissioner of the British Mandate of Palestine.

...

, the British War Office asked Bell for her assessment of the situation in Ottoman Syria, Mesopotamia, and Arabia. In response she wrote a letter detailing her thoughts on the degree of British sympathies in the region.

Bell volunteered with the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

, serving from November 1914–November 1915; first in Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

, France, and then later back in London. She was part of the Wounded & Missing Enquiry Department (W&MED) that attempted to coordinate information between the British Army, French hospitals, and worried families about the status of soldiers and casualties of the war.

Coincidentally, Judith Doughty-Wylie, the wife of the man Bell was carrying on an affair with, was also stationed in Boulogne in this period. The two met and exchanged pleasantries. Bell asked Charles Doughty-Wylie in a letter to discourage his wife from any further meetings.

Cairo, Delhi, and Basra

In November 1915, Bell was summoned to

In November 1915, Bell was summoned to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

in the British protectorate of Egypt; she arrived on 30 November. The Cairo detachment of British officials, headed by Colonel (later Brigadier General) Gilbert Clayton

Brigadier-General Sir Gilbert Falkingham Clayton (6 April 1875 – 11 September 1929) was a British Army intelligence officer and colonial administrator, who worked in several countries in the Middle East in the early 20th century. In Egypt, d ...

and renowned archaeologist and historian Lt. Cmdr. David Hogarth, was called the Arab Bureau

The Arab Bureau was a section of the Cairo Intelligence Department established in 1916 during the First World War, and closed in 1920, whose purpose was the collection and dissemination of propaganda and intelligence about the Arab regions of ...

. She also again met T. E. Lawrence, who had joined the Arab Bureau in December 1914. The Bureau set about organising and processing Bell's own, Lawrence's, and Capt. W. H. I. Shakespear's data about the location and disposition of Arab tribes of the Sinai and Gulf region. They also mapped the region, including its sources of water. This information would later be of use to Lawrence during the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

as to which tribes could be encouraged to join the British against the Ottoman Empire.

Bell's stay in Cairo was short; she was soon sent to British India, arriving in February 1916, likely at the suggestion of journalist-turned-diplomat Valentine Chirol

Sir Ignatius Valentine Chirol (28 May 1852 – 22 October 1929) was a British journalist, prolific author, historian and diplomat.

Early life

He was the son of the Rev. Alexander Chirol and Harriet Chirol . His education was mostly in Fr ...

. Her task in Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

was to better coordinate the Arab Bureau with the Government of India and mediate their differences; according to Bell, "there was no kind of touch between us except rather bad tempered written telegrams!" Lord Hardinge, Viceroy of India and family friend of the Bells, was skeptical of the Arab Bureau's recent moves and promises of an independent Arab state, fearing that directly challenging the Ottoman Sultan's religious role as caliph could stir up unrest among India's substantial minority of Muslims. Bell's knowledge of the issues impressed Lord Hardinge, and she was soon sent on to Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is hand ...

(captured by the British at the start of the war in November 1914) in March 1916 to act as a liaison between India and Cairo. At the time, the British were still recovering from recent setbacks in the Mesopotamian campaign

The Mesopotamian campaign was a campaign in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I fought between the Allies represented by the British Empire, troops from Britain, Australia and the vast majority from British India, against the Central Powe ...

. Her task there, as one of the very few Westerners who knew the area, was to advise Chief Political Officer Percy Cox

Major-General Sir Percy Zachariah Cox (20 November 1864 – 20 February 1937) was a British Indian Army officer and Colonial Office administrator in the Middle East. He was one of the major figures in the creation of the current Middle East.

...

, draw maps, find local guides willing to work with the British, and write reports on the inhabitants of Mesopotamia.

Cox found her an office in his headquarters, and she split her time between there and the Military GHQ Basra. She travelled in the region, assessed the stance and opinions of the local inhabitants, and drew maps that would aid the British Army in their eventual advance on Baghdad. Bell was unpaid at first, but Lord Chelmsford

Viscount Chelmsford, of Chelmsford in the County of Essex, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1921 for Frederic Thesiger, 3rd Baron Chelmsford, the former Viceroy of India. The title of Baron Chelmsford, of Chelm ...

arranged for her to be given a formal paid position in June 1916. She became the only female political officer in the British forces and received the title of Percy Cox's Oriental Secretary. During her Basra work, she struck up close working relationships with fellow political officers Reader Bullard

Sir Reader William Bullard (5 December 1885 – 24 May 1976) was a British diplomat and author.

Education

Reader Bullard was born in Walthamstow, the son of Charles, a dock labourer, and Mary Bullard. He was educated at the Monoux School th ...

and the young St. John Philby.

Bell met Ibn Saud

Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud ( ar, عبد العزيز بن عبد الرحمن آل سعود, ʿAbd al ʿAzīz bin ʿAbd ar Raḥman Āl Suʿūd; 15 January 1875Ibn Saud's birth year has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted ...

in Basra in late November–December 1916, as Cox and India were courting his support against the Ottoman-supporting Ibn Rashid

The Rasheed dynasty, also called Al Rasheed or the House of Rasheed ( ar, آل رشيد ; ), was a historic Arabian House or dynasty that existed in the Arabian Peninsula between 1836 and 1921. Its members were rulers of the Emirate of Ha'il a ...

. She was impressed with him and wrote an article in the ''Arab Bulletin'' extolling his abilities as a "politician, ruler, and raider." Ibn Saud was apparently less impressed with her; according to a later account by Philby, he mimicked her feminine and higher-pitched style of speech as an impression and joke to later Nejd audiences. She would later, in 1920, presciently warn Lawrence that he was overestimating Sharif Hussein's position after war between him and Ibn Saud broke out, and that Ibn Saud was likely to defeat the Hejaz if the struggle continued.

Armenian genocide

While in the Middle East, Gertrude Bell reported on the Armenian genocide. Contrasting the killings with previous massacres, she wrote that earlier killings "were not comparable to the massacres carried out in 1915 and the succeeding years." Bell also reported that in Damascus, "Ottomans sold Armenian women openly in the public market." In an intelligence report, Bell quoted a statement by a Turkish prisoner-of-war:Creation of Iraq

After British troops took Baghdad, on 11 March 1917, Bell was summoned by Cox to the city. She was also given the honour of Commander of theOrder of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

. After Cox left Mesopotamia in 1918 for England and then Persia, control fell to Arnold Wilson

Sir Arnold Talbot Wilson (18 July 1884 – 31 May 1940) was a British soldier, colonial administrator, Conservative politician, writer and editor. Wilson served under Percy Cox, the colonial administrator of Mesopotamia (Mandatory Iraq) ...

, the Acting British Civil Commissioner in Mesopotamia. Initially, Bell and Wilson got along; a memorandum Bell wrote in February 1919, "Self-Determination in Mesopotamia", did not show major differences with Wilson. Cox and Wilson's wartime provisional government drew on British India for inspiration, replicating its legal code and bureaucratic structure, and Bell's assessment was that this was keeping the Iraqi people content. Bell visited France and England in 1919, attending the Paris Peace Conference for a short time in Wilson's stead. At Paris, plans for the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire came into shape, as negotiations over which territories should be distributed to who took place. Famously, the Sykes–Picot Agreement, negotiated by the same Mark Sykes whom Bell had met 15 years earlier, allocated northern Syria to French influence, although the French were persuaded to withdraw their claims on Mosul vilayet to Syria's east. This left the British and Arabs with southern Syria, Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra to divide.

Bell spent September–October 1919 visiting Egypt, Palestine, and Hashemite-ruled Syria before returning to Baghdad in November 1919.

In 1919, Mesopotamia was still under a provisional military government that largely reported to the government of British India. Over the course of 1919, Bell became convinced that an independent Arab government in Mesopotamia backed by British advisors was the correct path to follow. She saw the provisional Hashemite government in Syria, while corrupt, seemingly return life to a peaceful normal state; meanwhile, affairs in Egypt saw the Egyptian Revolution of 1919

The Egyptian Revolution of 1919 ( ''Thawra 1919'') was a countrywide revolution against the British occupation of Egypt and Sudan. It was carried out by Egyptians from different walks of life in the wake of the British-ordered exile of the r ...

against the British. Bell believed that the "spirit of 1919" would spread to Mesopotamia as well if the British dawdled in honouring the promise of self-determination. She spent nearly a year writing what was later considered a masterly official report, "Review of the Civil Administration of Mesopotamia". Civil Commissioner Wilson disagreed with Bell on the topic, and the two had a falling out. Wilson, of the India school, preferred an Arab government to be under direct influence of British officials who would retain real control, as he felt, from experience, that Mesopotamian populations were not yet ready to govern and administer the country efficiently and peacefully. Troubles arose; Shia tribes in central Iraq rose in revolt in the summer of 1920, and made common cause with Sunnis. Wilson blamed Sharifan anti-British propaganda for the revolt. Bell blamed Wilson for the unrest in the region, saying his approach was insufficiently deferential to local wishes.

On 11 October 1920, Percy Cox returned to Baghdad, replacing the discredited Wilson. Cox asked Bell to continue as his Oriental Secretary and to act as liaison with the forthcoming Arab government. Cox promptly restored much of the earlier Ottoman government structure and began to appoint more Iraqis to lead in the local provincial governments, albeit backed by powerful British advisors. Back in the British Isles, the British public was weary of constant war, the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

was being fought, and the British Empire was deeply in debt following the ruinous Great War. British officials in London, in particular the new Secretary of State for War and Air, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, wanted to reduce expenses in the colonies, including the cost of quashing revolts. British officials realised that their policy of direct governance was adding to costs. While the revolt of 1920 was successfully suppressed, it had cost 50 million pounds, hundreds of British and Indian lives, and thousands of Arab lives to do so. It was clear that Iraq would be cheaper as a self-governing state. Churchill convened a conference in Cairo to resolve the future of British administration of the region now that the war was finished.

1921 Cairo Conference

Bell, Cox and Lawrence were among a select group of "Orientalists" convened by Churchill to attend the conference in Cairo to determine the internal boundaries of the British mandates from within the territory Britain had claimed during the

Bell, Cox and Lawrence were among a select group of "Orientalists" convened by Churchill to attend the conference in Cairo to determine the internal boundaries of the British mandates from within the territory Britain had claimed during the Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 19181 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was ...

. Few British officials had any experience in Arab or Kurdish affairs; Cox trusted Bell, and Bell was thus unusually influential and gave significant input in these discussions. The British government had reluctantly allowed France to take control of Syria as part of negotiations of the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

, leading to the creation of the French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

. This complicated earlier British promises to its allies in the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans, as they had presumed they would lead a new pan-Arab state centred in Damascus; but the French saw the Hashemites and their allies as potential rivals for power, and thus had no interest in allowing a Hashemite monarchy in Syria.

Various possibilities existed for these lands, including a continued direct mandate (the British Mandate for Mesopotamia), independence on various terms, or even ceding the discontented northern territories back to the new Turkish state. The school of thought that favoured independence with British direction and alliance became known as the "Cairo School", against the "India School" that favoured direct rule by Britons. Throughout the conference, Bell, Cox, and Lawrence favoured the Cairo School approach, and worked to promote the establishment of the independent countries of Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

and Iraq. They also supported the Sharifian Solution

The Sharifian or Sherifian Solution, () as first put forward by T. E. Lawrence in 1918, was a plan to install three of Sharif Hussein's four sons as heads of state in newly created countries across the Middle East: his second son Abdullah ruling ...

: that these states be presided over by the sons of the instigator of the Arab Revolt, Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca

Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi ( ar, الحسين بن علي الهاشمي, al-Ḥusayn bin ‘Alī al-Hāshimī; 1 May 18544 June 1931) was an Arab leader from the Banu Hashim clan who was the Sharif and Emir of Mecca from 1908 and, after procl ...

. In this proposal, Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

and Faisal would serve as the kings of the new countries (the eventual Monarchy of Jordan and Monarchy of Iraq). Bell thought that Faisal's status as an outsider would enable him to hold together the new country of Iraq as someone not beholden to any one group, but rather a unifying symbol. In theory, Shias would respect him because of his lineage from Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

; Sunnis would follow him because he was Sunni from a respected family. In practice, pan-Arabism and Sharifism would prove more appealing to the Sunni population in Iraq than the Shia population. Bell was also influenced by a strain of British thought that romantically considered the desert Arabs of the Hejaz as "pure" Arabs, and thus naturally suited to possessing legitimacy and respect; the success of Faisal in the Arab Revolt at assembling a coalition of disparate tribes acted as proof to this school.

The Ottomans had divided the region into the strategically important for the British Basra vilayet in the south, the central Baghdad vilayet

ota, ولايت بغداد''Vilâyet-i Bagdad''

, conventional_long_name = Baghdad Vilayet

, common_name = Baghdad Vilayet

, subdivision = Vilayet

, nation = Ottoman Empire

, year_start = 18 ...

, and the northern Kurdish-dominated Mosul vilayet. The three had little cultural or economic interdependency under Ottoman rule. The territory of the new Iraq was an undecided matter before the conference. The question of what to do with oil-rich Mosul in particular became known as the Mosul question

The Mosul question was a territorial dispute in the early 20th century between Turkey and the United Kingdom (later Iraq) over the possession of the former Ottoman Mosul Vilayet.

The Mosul Vilayet was part of the Ottoman Empire until the end of ...

. Bell advocated for expansive Iraqi borders that would include all three of the Ottoman territories including Mosul. In this, she was defeated at the conference; Churchill, Hubert Young, Lawrence, and others feared that putting Kurds under an Arab ruler might make them sympathetic to Turkey and disloyal to Iraq, while establishing an independent buffer state of Southern Kurdistan or Upper Mesopotamia would ensure the Kurds would see any Turkish incursion as unwelcome rather than a liberation. They insisted that the Southern Kurds only be included in Iraq if they directly asked to be. Bell would eventually get her way after the conference, though. In the process of the largely performative nationwide referendum to endorse Faisal of 1921, the referendum takers were able to find enough pro-Faisal members of Kurdish elite to satisfy the new British government of late 1922 to allow the inclusion of Mosul as part of Iraq after all. The Kurdish elite had extracted certain promises for autonomy, but these promises would be largely ignored. Bell wrote a letter in 1924 responding to an article likely from Arnold Wilson that argued Mosul would be happier under Turkish rule; Bell argued that based on the elite representatives to the Constituent Assembly, Mosul still wished to be part of Iraq. Negotiations and occasional warfare with Kemalist Turkey would continue until 1926, when the Treaty of Ankara recognized Mosul as part of Iraq. Lawrence would later write that he often feared and sometimes hoped that the over-large state Bell had built would collapse.

Against the wishes of the Arab-sympathetic Bell, the British would eventually decide to keep the British Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. The manda ...

to be run directly by themselves, rather than make it part of Transjordan. Bell opposed the Zionist movement

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Jew ...

; she wrote that she regarded the Balfour Declaration with "the deepest mistrust" and that "It's like a nightmare in which you foresee all the horrible things which are going to happen and can't stretch out your hand to prevent them". In a letter to her mother she described the Balfour Declaration as "a wholly artificial scheme divorced from all relation to facts and I wish it the ill-success it deserves".

Advisor to Faisal

The Sharifan solution prevailed, and Faisal was presented to Iraq as the new king. The main local candidate for leadership who had opposed the selection of Faisal, Sayyid Talib, was arrested and exiled in April 1921 after being invited to tea with Percy Cox's wife, at Bell's suggestion and with Cox's assent; Bell viewed Talib as a potential rebel if left unchecked.

Bell served in the Iraq British High Commission advisory group throughout the 1920s and was an integral part of the administration of Iraq in Faisal's first years. Upon Faisal's arrival in 1921, Bell advised him on local questions, including matters involving tribal geography, tribal leadership, and local business. Faisal was crowned king of Iraq on 23 August 1921. Referred to in

The Sharifan solution prevailed, and Faisal was presented to Iraq as the new king. The main local candidate for leadership who had opposed the selection of Faisal, Sayyid Talib, was arrested and exiled in April 1921 after being invited to tea with Percy Cox's wife, at Bell's suggestion and with Cox's assent; Bell viewed Talib as a potential rebel if left unchecked.

Bell served in the Iraq British High Commission advisory group throughout the 1920s and was an integral part of the administration of Iraq in Faisal's first years. Upon Faisal's arrival in 1921, Bell advised him on local questions, including matters involving tribal geography, tribal leadership, and local business. Faisal was crowned king of Iraq on 23 August 1921. Referred to in Iraqi Arabic

Mesopotamian Arabic, ( ar, لهجة بلاد ما بين النهرين) also known as Iraqi Arabic ( ar, اللهجة العراقية), or Gilit Mesopotamian Arabic (as opposed to North Mesopotamian Arabic, Qeltu Mesopotamian Arabic) is a contin ...

as "al-Khatun" (a Lady of the Court), Bell was a confidante of Faisal and helped ease his passage into the role. Bell played the role of mediator between Faisal's government, British officials, and local notables. She took a special interest in public relations: arranging receptions, parties, and meetings; discussing the state of affairs with both the British and Arab elite of Baghdad; and transferring requests and complaints to the government. She also suggested designs for both the flag of Iraq

The flag of Iraq ( ar, علم العراق Kurdish languages: الله اكبر) includes the three equal horizontal red, white, and black stripes of the Pan-Arab colors, Arab Liberation flag, with the phrase "Allahu Akbar, God is the greatest" ...

and Faisal's personal flag.

The new Iraqi government had to mediate between the various groups of Iraq: Shias, Sunnis, Kurds, Jews, and Assyrian Christians. Keeping these groups content was essential for political balance in Iraq and for British imperial interests. An important project for both the British and the new Iraqi government was creating a new identity for these people so that they would identify themselves as one nation. One of the main issues that faced Faisal was establishing his legitimacy among the Shia population. There was little enthusiasm for Faisal when he landed at the Shia port of Basra. Faisal's administration, while reserving certain positions for Shiites as a token, was pan-Arabist and Sunni-dominated, a position that Bell endorsed. Sunni elites made it clear that they would consider any reduction of their traditional privileges during Ottoman rule, as compared to the Shiites or Kurds, a betrayal. Bell thought that a Shia-dominated government would likely devolve into a theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy origina ...

. Bell had difficulty making close relationships with the most important Shia leaders; she wrote that she was "cut off from them because their tenets forbid them to look upon an unveiled woman and my tenets don't permit me to veil

A veil is an article of clothing or hanging cloth that is intended to cover some part of the head or face, or an object of some significance. Veiling has a long history in European, Asian, and African societies. The practice has been prominent ...

."

Bell did not find working with the new king to be easy; she wrote in one 1921 letter that "You may rely upon one thing — I'll never engage in creating kings again; it's too great a strain."

National Library of Iraq

Muriel Forbes advocated for the creation of a new library in Baghdad in 1919–20 and founded the Baghdad Peace Library (''Maktabat al-Salam''). Bell energetically promoted the library and subsequently served on its Library Committee as President from 1921 to 1924. This included participating in fund-raising events, soliciting free copies of books from British publishers for library use, and publishing articles in the library's Review. The library started as a private, subscription library, but due to financial difficulties, it was taken over by the Ministry of Education in 1924 and changed into a public library. In 1926, it was one of only two public libraries in the country. It became known as the Baghdad Public Library in 1929, and was renamed in 1961 to the National Library of Iraq.Director of Antiquities

Assyriologist

Assyriology (from Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , ''-logia'') is the archaeological, anthropological, and linguistic study of Assyria and the rest of ancient Mesopotamia (a region that encompassed what is now modern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southea ...

Edward Chiera

Edward Chiera (August 5, 1885 – June 20, 1933) was an Italian-American archaeologist, Assyriologist, and scholar of religions and linguistics.

Born in Rome, Italy, in 1885, Chiera trained as a theologian at the Crozer Theological Seminary (B. ...

to conduct archaeological excavations in ancient Nuzi

Nuzi (or Nuzu; Akkadian Gasur; modern Yorghan Tepe, Iraq) was an ancient Mesopotamian city southwest of the city of Arrapha (modern Kirkuk), located near the Tigris river. The site consists of one medium-sized multiperiod tell and two small s ...

, near Kirkuk

Kirkuk ( ar, كركوك, ku, کەرکووک, translit=Kerkûk, , tr, Kerkük) is a city in Iraq, serving as the capital of the Kirkuk Governorate, located north of Baghdad. The city is home to a diverse population of Turkmens, Arabs, Kurds, ...

, Iraq, where hundreds of inscribed clay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets ( Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a sty ...

s had been discovered and deciphered, now known as the Nuzi Tablets.

1924 Antiquities legislation

The state of approvals for archaeological digs during Ottoman Empire rule had been loose and unorganized; digs happened without being registered to any authority; and there was no governing body with the authority to oversee or enforce the few regulations that did exist. Bell's chief role as Director of Antiquities was to draw up proposed legislation that would clarify the status of existing digs, regulate the granting of new permits, adjudicate ownership of discovered artefacts, and allow for the creation of a Department of Antiquities to enforce the law. Bell's initial proposals were considered overly friendly to British interests bySati' al-Husri

Sāṭi` al-Ḥuṣrī, born Abu Khaldun Sati' al-Husri,( ar, ساطع الحصري, August 1880 – 1968) was an Ottoman, Syrian and Iraqi writer, educationalist and an influential Arab nationalist thinker in the 20th century.

Early life

Of Sy ...

, Faisal's Director of Education and an Arab nationalist. Al-Husri slowed passage of the law, but Bell's law passed in 1924 after revisions; it largely followed the standard model elsewhere in the world, but notably reserved extensive power to the Director (that is, herself) to judge whether discovered antiquities would go in the national museum and stay as property of the state, or be allowed for export. It also placed the Department of Antiquities under the Ministry of Public Works, away from al-Husri.

Bell's law was a hybrid that bridged the gap between the chaos of Ottoman-era archaeology and later laws that would more directly enforce Iraqi sovereignty on the matter. Foreign archaeologists continued legally exporting antiquities from Iraq, but in a more restricted manner. Simply organizing, tracking, and regulating archaeological digs seems to have hurt the black market trade in looted antiquities.

Baghdad Archaeological Museum

As Director of Antiquities, Bell was responsible for storing excavated antiquities for personal review and examination. Her initial storeroom, called the Babylonian Stone Room, was soon filling up, however. She requested a dedicated building to act as a museum in March 1923, but was initially rejected. After sustained lobbying effort over the next years, carefully ensuring that the elites of Iraqi government and society saw the latest excavations from Ur and were invested in the project at parties and events, she finally secured a location for her museum plan on the ground floor of a stationery and printing building in March 1926. This became the Baghdad Archaeological Museum, later renamed theIraq Museum

The Iraq Museum ( ar, المتحف العراقي) is the national museum of Iraq, located in Baghdad. It is sometimes informally called the National Museum of Iraq, a recent phenomenon influenced by other nations' naming of their national museum ...

; it opened in June 1926, shortly before Bell's death.

As part of her role as Director, Bell helped establish procedures that were becoming standard around the world: carefully keeping a ledger of excavations and finds, as well as detailed descriptions of material, dimensions, and other comments; applying a formal numbering system to track them; and sending photographs of unusual finds off to the British Museum for further analysis. She did this with only a small but hard-working staff; the Department of Antiquities only consisted of her, Abdulqadir Pachachi, and Salim Lawi from 1924–26. Bell and the Department helped preserve Iraqi culture and history which included the important relics of Mesopotamian civilizations, and the museum kept them in their country of origin. Bell's will bequeathed £50,000 to the Iraq Museum and £6,000 to the British Museum to establish the "British School of Archaeology in Iraq" in London (later renamed to "The British Institute for the Study of Iraq"), which continued to fund and aid excavation projects (adjusted for inflation, around £2.1 million and £250,000 in 2021, respectively).

Final years

The stress of authoring a prodigious output of books, correspondence, intelligence reports, reference works, and white papers; of recurringbronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

attacks brought on by years of heavy cigarette smoking; of bouts with malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

; and finally, of coping with Baghdad's summer heat all took a toll on her health. Somewhat frail to start with, she became emaciated over the course of the 1920s, and suffered a drastic collapse of her health in 1924."Letters from Baghdad" documentary (2016) Directors: Sabine Krayenbühl, Zeva Oelbaum. Bell briefly returned to Britain in 1925, where she faced continued ill health. She did take the opportunity to correspond with Lawrence, who sought her advice on his forthcoming book ''Seven Pillars of Wisdom

''Seven Pillars of Wisdom'' is the autobiographical account of the experiences of British Army Colonel T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), of serving as a military advisor to Bedouin forces during the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire ...

''. Her family's fortune had begun to decline due to a wave of post-World War I coal strikes in Britain that would culminate in the general strike of 1926

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British governmen ...

and economic depression in Europe; the Bells began preparation to move out of their expensive mansion at Rounton to reduce costs. She returned to Baghdad and soon developed pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other sy ...

. While she recovered, she heard that her younger half brother Hugo had died of typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

.

Many of Bell's dear friends left Iraq in the early 1920s, most notably Percy Cox, who retired in 1923. In late 1922, she struck up a lasting friendship with Kinahan Cornwallis

Sir Kinahan Cornwallis (19 February 1883 – 3 June 1959) was a British administrator and diplomat best known for being an advisor to King Faisal I of Iraq and for being the British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Iraq during the Anglo-Iraqi ...

, a fellow British advisor in Iraq. She signaled an openness to a romantic involvement to the much younger Cornwallis, but was rejected, and their relationship stayed a professional friendship.

Bell suffered psychologically from 1923–1926, and may have been depressed. The new High Commissioner of the mandate installed in 1923, Henry Dobbs

Sir Henry Robert Conway Dobbs (26 August 1871 – 30 May 1934) was an administrator in British India and High Commissioner in Iraq.

Career

Dobbs was educated at Winchester College and Brasenose College, Oxford. He joined the Indian Civil Servic ...

, kept Bell as his Oriental Secretary but consulted her less frequently than Percy Cox had. Bell was no longer consulted by Faisal as much after his first year in office either, and he had not lived up to her impossibly high expectations. While she had thrown herself into her new position as Director of Antiquities with gusto, she still disliked being sidelined from the high affairs of state. Over the course of two days in 1925, her beloved pet dog as well as Kinahan Cornwallis's dog, whom she had looked after and cared for as well, both died.

On 12 July 1926, Bell was discovered dead of an overdose of allobarbital sleeping pills

Hypnotic (from Greek ''Hypnos'', sleep), or soporific drugs, commonly known as sleeping pills, are a class of (and umbrella term for) psychoactive drugs whose primary function is to induce sleep (or surgical anesthesiaWhen used in anesthesia ...

. It is unknown whether the overdose was an intentional suicide or an accidental misdose. She had asked her maid to wake her in the morning, suggesting an accident, but she had also requested for Cornwallis to look after her new dog in case anything happened to her the previous day, and had recently written a philosophical letter on how her lonely existence cannot extend forever to her mother, suggesting foreknowledge of her death. She was buried at the Anglican cemetery in Baghdad's Bab al-Sharji district the same day. Her funeral was a major event, attended by a large crowd. It was said King Faisal watched the procession from his private balcony as they carried her coffin to the cemetery. Back in Great Britain, King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

personally wrote a letter of condolences to her parents Hugh and Florence.

Views and positions